The sun is beating down from the wide Limpopo sky and my limbs take on the familiar kind of heaviness they always seem to do when confronted with unfamiliar heat. Apart from a thin sliver steadily crawling back toward the tiny square building from which it has been cast and a spreading acacia tree, the clean-swept yard dotted with ethereal wooden sculptures of aquatic beings and religious figures is almost utterly devoid of shade. So, we all huddle in the patches we can find. That is until Patrick Manyike, owner of the property, calls us over to where he stands behind his humble home, atop a heap of red earth. This is no termite mound, it turns out, but rather a small hill of heavenly hope.

“This… this is my vision,” he announces serenely, gesturing to the rough outlines of a foundation beneath his feet. “Here, I will build my workshop and my gallery, where people can come and look at my work and buy the pieces they like.”

You see, Patrick is a woodcarver with a passion for his craft that burns with an otherworldly fire in his eyes. I listen – entranced – as he shares his dream with us and the heat of the day dissipates. His infectious energy catches on and suddenly my leaden limbs are light once more. “I’ve tried doing normal jobs a few times in my life. But it never works out, because the wood always calls me back. I’m free when I’m carving.”

He tells us about the one month he worked as a cleaner at Carnival City in Johannesburg and how he’d spend his days mopping up overturned popcorn and spilled drinks in movie theatres. And how at the end of that month, when he finally got his pay check and a weekend off, he didn’t think twice about returning home to set his broom-weary hands to work on what they were always meant to do: ‘cleaning the wood’ instead. Interestingly, much of Patrick’s work seems to follow an aquatic theme and we ask him about the fish and crocodiles and mermaids swimming around his yard. He explains that, to him, these creatures are a symbol of sustenance. Just like in the Bible, where Jesus multiplies the five loaves and two fish to feed the 5 000 who followed him to Bethsaida, you will always find tins of sardines or tuna or pilchards in the nearby spaza shops, even on days when they don’t have bread. Something about the fluidity of his sculptures also suggests that he never forces a figure into being and soon enough he explains this too: “When I find a piece of wood, me and the wood start communicating. I put it somewhere and look at it and as time goes on, I see what’s inside,” he explains.

“Like this piece,” he says, reaching out and touching a tall column of leadwood standing in front of him, “here I can see an old man who can’t walk properly like before. That’s the bond between me and the wood.”

Once the figure presents itself to Patrick, he starts following the contours of the story to carve away the excess. Referring to the old man still stuck in his leadwood prison, Patrick concludes: “I see inside here is madala. So, my duty… for me, my duty is to remove what is not important, so that I am left with what? With madala.”

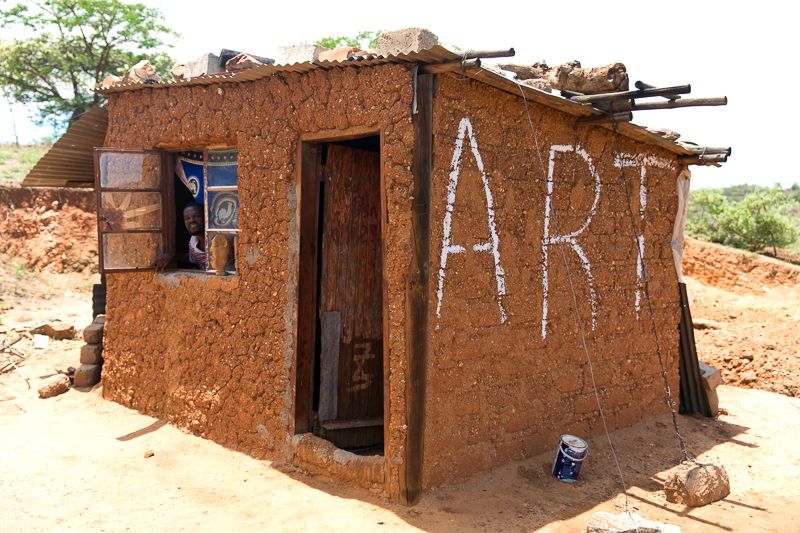

To Patrick this is his simple life task. To me, it resonates as a mystical mantra that encapsulates every aspect of life. Removing what’s not important, so you can be left with what is. “I’m not doing this for me,” he says. “It’s a job of God for me to do. It must make the heart feel good. That’s my secret.” While Patrick’s visionary studio space and gallery is still in the making, he does his carvings in the clean swept yard. Those that stay outside, he coats in used car oil to protect them from the harsh sun and summer rains, while the rest line a set of shelves in his little home – neatly made bed in the corner – that doubles as a shop.

You can visit Patrick too and even spend a morning learning how to carve with him, as part of the Get Crafty in Mbhokota experience on Open Africa’s Ribola Art Route.